Undeleting Music

Many years ago, my friend Andrew Dubber had a great blog he called Deleting Music. It’s gone now but essentially it was concerned with the way much of the music created over the years was slowing disappearing. It was a very important blog for the times, in part, because at the time his Deleting Music was created, the big news was the rapid growth of Apple’s iTunes which seemed to be making a lot of old music available again.

Or was it? The truth was that it was selective and as I said in a post on my own Opinionated Diner blog, I was driven to make my own comment, for several reasons:

Firstly there is the release of Chris Bourke’s monumental history of pre-and early rock’n’roll musical history, Blue Smoke. Buy it please. Enjoy it — you will. Immerse yourself in the music — you can’t. Nope almost everything he writes about in the book is unavailable. You can’t buy it. You can’t even steal it online. The same is true of the overwhelming bulk of the music I listed last year on my Zodiac page. And much of John Dix’s Stranded in Paradise.

The simple truth was that most of what had been released in New Zealand since we started recording music and releasing it locally in 1949 was unavailable in any format. I pleaded there for a music archive (which arrived in several forms via AudioCulture and the recent mastertapes preservation drive from New Zealand’s National Library) to save our music before it was too late. These two vehicles told our stories and, initially at least, started the task of saving our physical recordings for future generations. However, they did not fulfill the other key task of making the music publicly available again.

There, several other factors I could not have envisaged in 2010, came into play. Firstly, in 2012, the ailing EMI, the local branch of which was the longest operating record company in New Zealand, dating back to 1926, and one that controlled much of the nation’s musical past, was taken over globally by the multi-national Universal Music Group. I expressed concern about that impending takeover here and said:

It’s terrifying and there is absolutely no way any one record company can understand, curate or do justice to a catalogue of that volume.

In New Zealand, specifically, that meant that Universal Music New Zealand now owned much of the country’s recorded history even if most of it was unavailable. Universal was the successor to PolyGram which was purchased by the then Canadian owned company at the end of 1998. That meant that Universal NZ owned the local catalogue issued originally on Polydor, Philips, Vertigo, Fontana and Mercury as well as their own Universal and MCA labels. To that ,in 2012, they added a very large number of local releases originally issued on EMI, His Master’s Voice, Harvest, Regal, Parlophone, Columbia (the EMI version) and World Record Club.

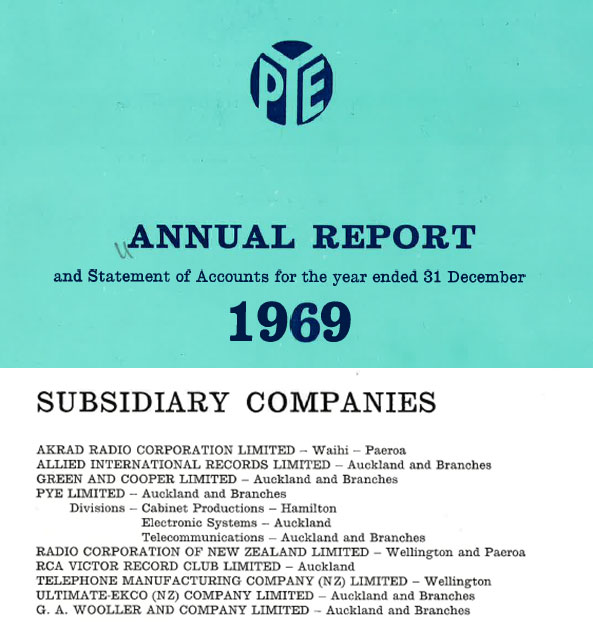

My understanding was that Universal also owned the NZ created catalogues of Pye, once the third biggest record company in New Zealand with a catalogue that dated to 1949 and one that had grown over the years with acquisitions, but Universal’s NZ boss Adam Holt was a little unsure about that. We will come to that shortly.

Another factor I had not envisaged in 2010 was the arrival of digital streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music which provided an easier way of sharing data. They grew at a massive rate and were aided by companies called aggregators who serviced all the outlets. Universal, being the giant they are, have their own aggregator.

Adam Holt’s response to this vast catalogue he now oversaw was to determine that all Universal’s local catalogue should be made available again digitally even though he was aware that this would be both costly and very time consuming. It was, he felt, culturally responsible of Universal New Zealand as the guardian of much of New Zealand’s musical past. Everything, even music that had gone into public domain, was to be digitised and royalties would be paid where the artist could be found, and at current rates. It would require a dedicated person.

Enter, Chris Caddick, the former head of EMI New Zealand, active in the New Zealand music industry since the late 1970s, who was, by the early 2010s, the board chair of Recorded Music New Zealand, the NZ industry body. In 2012, Chris had commenced a project he called Tied To The Tracks largely as an anti-piracy measure. The idea was that RMNZ and its member companies would digitise as many major releases from the last five decades as they could and place them on the various services. By mid-2014, they had successfully put 230 albums online and a public launch and media blitz was undertaken in which Chris committed to taking the number to five hundred in the next few years.

Adam Holt asked Chris to assist with a Universal New Zealand programme that would not only put all their important catalogue online but eventually see 100% of everything they owned which was recorded in New Zealand or by New Zealanders online. Chris agreed but there was one significant hurdle, defining the chain of ownership of many of the companies and labels PolyGram and its predecessor had acquired or absorbed over the years inside New Zealand. In particular the Pye conglomerate which had, in its turn, absorbed several other companies and recorded its repertoire on a variety of labels, some unlikely.

That’s where I came in and I was asked if I could prove Pye’s catalogue was owned by the local company, which I did using my own personal archival records and supporting documents in Archives NZ and other governmental and local goverment archives. I was able to show that not only did Universal New Zealand own Pye’s domestic recordings including classics like the two Human Instinct albums and one Underdogs album recorded for AIR, they also owned the landmark Tanza label (responsible for the very first NZ artist release in NZ, ‘Blue Smoke’ from early 1949), Phil Warren’s Prestige, Allied International, the Family label, NZ artists released on RCA in the 1960s (Pye had RCA in NZ then and used the brand liberally, probably without the US licensor knowing) and NZ’s Top Rank imprint.

By mid-2018, I was able to satisfy, with documents, Adam and Chris’ chain of evidence. With that, Universal NZ embarked on this incredibly ambitious to put every single New Zealand 45, 12”, LP, cassette and CD their labels had ever released online – and pay the artists where possible.

By the end of 2019, Chris and Adam had completed almost all the albums, having sourced the best copies, remastered each one, added bonus tracks if they existed and made every possible effort to contact the artist or their relatives. The artwork had also been refreshed by RMNZ's Mark Roach.

However, they'd also taken this one step further when Adam reached an agreememt with Universal Australia (its head George Ash is a New Zealander) that allowed the New Zealand company to reissue recordings made in Australia by New Zealanders owned by the Australian company. That added unavailable albums by acts like The La De Da's, Claude Papesch, Allison Durbin and many others to the online catalogue.

The New Zealand labels (with the dates they issued NZ artist catalogue):

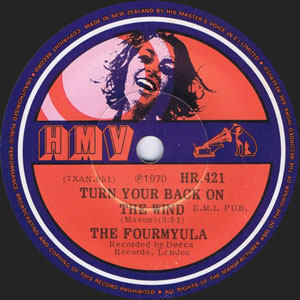

- His Master’s Voice (1949-73)

- Tanza (1949-59)

- Pye (1965-75)

- Top Rank (1959-61)

- Prestige (1957-60)

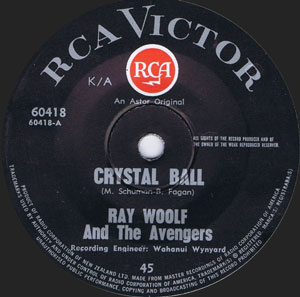

- RCA (1965-70)

- Nixa (1960)

- Allied International (1961-68)

- Philips (1961-90)

- Polydor (1967-98)

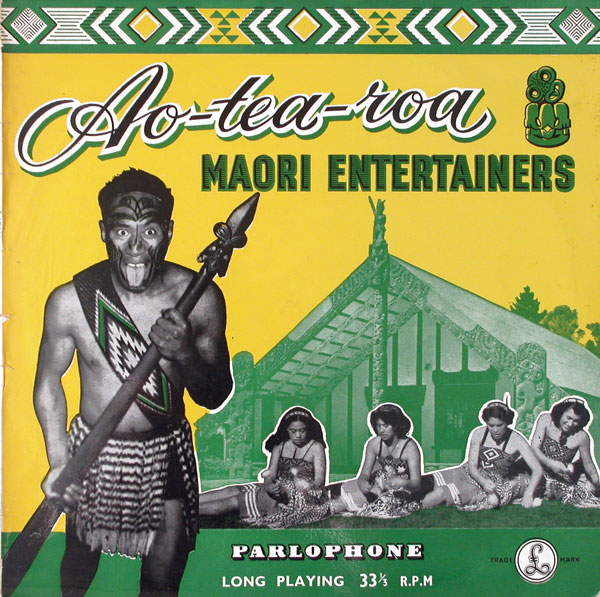

- Parlophone (1927-30, 1956, 1960, 1964-65)

- Columbia (1930, 1958, 1968-70)

- Regal (1968-72)

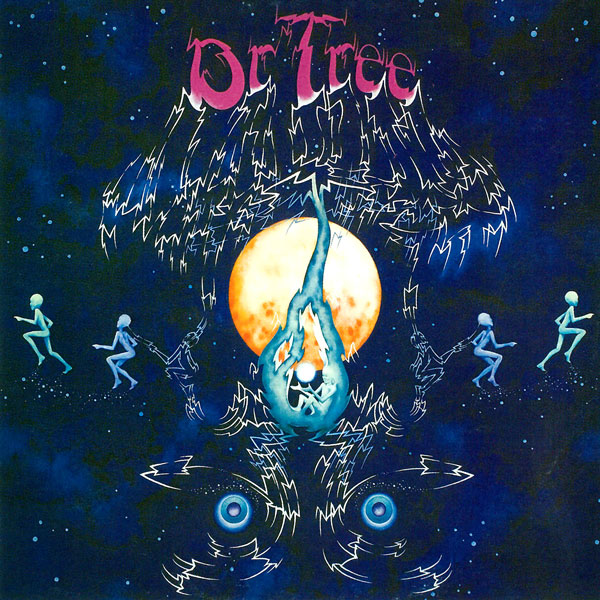

- Harvest (1970-73)

- EMI (1973-2012)

- World Record Club (1964-80)

- AIR (1970-73)

- Karussell (1972-75)

- Vertigo (1970-83)

- Mercury (1991-94)

- Family (1972-75)

- Marble Arch (1969)

- MCA (1968-70)

- Universal (1996-)

- Shoestring (1973-74)

They had, by this time, digitised some 393 albums from the catalogue. The next step was the stray tracks by artists who had never made albums. There are a large number.

Chris Caddick:

We made a pragmatic decision to concentrate on everything issued on 7” and 12” onwards (i.e. after 78s). I’ve compiled 19 x 30-40 track compilations of singles (A&B sides) and they are next.

From a cultural and archival point of view, the work undertaken by Chris Caddick to date is both globally unique and, given that it embraces perhaps 60% of all music recorded in New Zealand by New Zealanders up to 2012, and a far, far, higher percentage from 1927 (when the first released recordings of New Zealanders in New Zealand were done) to 1970, vitally important in defining who we are musically. Its cultural import is immense.

Adapted from an article written for The Lost Record Stores of New Zealand, April 2020.